Eve so far

Jamie Brandon - 16 Oct 2014

This is the Eve development diary.

The goal of Eve is to give everyone access to computing as a general purpose tool. Languages and tools aimed at programmers require an inordinate investment of time and effort to reach basic competence. Environments aimed at non-programmers impose a low ceiling on power and have not caught up to modern computing (support for real-time collaboration, sharing data between programs, building web applications etc). We aim to build a computing environment that supports beginners and experts equally.

While Eve is constantly changing as we learn more, there are a number of design principles that we take as axiomatic:

Grow with the user. The way to introduce a complex skill is to teach it gradually. Beginners should be presented with a simple interface. More complex features should be unlocked as they are needed. This allows simple tasks to be easily learned without imposing a ceiling on power.

Belong to the user. Advanced users should be able to understand and extend the environment itself. That means it must be open source, have a simple and well documented implementation and be designed for extending. We should encourage users to learn by reducing the number of steps it takes to go from having a question about a tool to opening the hood and poking around inside.

Be friendly and helpful. There should always be an obvious path from encountering a new problem to finding answers. Exploration and experimentation should be encouraged by teaching the user that every action is safe and can be undone. Error messages should be accompanied by a full explanation and suggestions for how to proceed.

Ergonomics matter. We should observe users and collect data to discover common actions and workflows. The environment should be optimised for the way that people use it, not the way that we think it should be used. Tools should communicate with each other instead of making the user perform the same actions manually e.g. consider the number of manual steps between seeing an error in production and reproducing it in a debugger - the ideal interaction is just clicking on the error in some dashboard and being dropped into a debugger with the same runtime state.

Computing is the means, not the end. Most end-users are not here to program for the sake of programming; they are trying to solve some problem in the real world. Every tool and feature must demonstrably and immediately save the user time and effort or they will ignore it. A simple tool that solves 80% of the users problems is often preferable to a complex tool that tries to do everything and requires a manual the size of a house.

Empiricism over ideology. If something doesn’t work in practice, it doesn’t work at all. We shouldn’t make assumptions about what users will understand or how they ‘naturally’ think. We should be aware of our history - of what has and hasn’t worked in the past and the reasons why. The real world exists, it is a mess and it won’t go away if we close our eyes and ignore it.

This diary will be updated once a month and will track our successes and, more importantly, our failures. We will start by retroactively filling in the months since the project began.

The Beginning

Eve began life as Aurora, a demo of a live environment for a clojure-like language that Chris cooked up on a flight to Strange Loop in September 2013. Light Table was reaching the limits of what it could do with traditional languages and Chris wanted to see how far he could push the same ideas in a language designed for the task.

January 2014

In early January, Light Table was open-sourced and work began on turning the Aurora demo into a usable prototype. We were pretty certain that all that really needed to be done to make programming accessible was to make the data visible and directly manipulable. “It’ll be over by Christmas.”

The initial language was a clojure-like pattern-matching functional language run in a simple interpreter. Outputs were updated live as input data changed, using traditional SAC.

There was only a single global tree data-structure that was traversed and modified by the program. Every piece of state in the program had to live somewhere in this tree. Input was added into a special location in the data-structure and output was read from another. Functions could be passed ‘cursors’ that allowed them to mutate part of the tree, creating a kind of mutable variable. These cursors could not be stored in the tree itself so it was not possible to create cycles.

The UI hadn’t changed much from the initial demo at Strange Loop. We showed a collapsible tree of functions alongside the input and output data for each function. There was always tension between whether we should display the control flow of an actual execution or the abstract control flow of the function itself.

The good:

- All state was accessible and browsable from the root of the tree. The ease of debugging and understanding that we experienced led to the heretical idea that perhaps encapsulated state is actually harmful

- Every function had a unique id. The names displayed on the screen were just documentation. There were no namespaces and renaming a function just required changing the name tag attached to the id.

- The SAC-like model made it easy to immediately see the effects of changes to data or code. Tight feedback loops make for easy debugging.

The bad:

- Hierarchical organisation of data complects the data itself with the common access paths. If any of us had lived through the years of network/xml/object databases we would have known this already. Paying attention to history would have saved us some time.

- Passing cursors quickly became tedious when trying to change code. If a function suddenly needed access to IO the cursor had to be passed down through every function above it in the callstack. Manual, non-local propagation of changes is a sign of strong coupling. Seeing it show up in our state and IO models was a bad sign.

The ugly:

- Excited, we presented our prototype to a small number of non-programmers and sat back to watch the magic. To our horror, not a single one of them could figure out what the simple example program did or how it worked, nor could they produce any useful programs themselves. The sticking points were lexical scope and data structures. Every single person we talked to just wanted to put data in an Excel-like grid and drag direct references. Abstraction via symbol binding was not an intuitive or well-liked idea.

Back to the drawing board.

February 2014

The big sticking points that we identified were lexical scoping, data structures and hierarchical organisation.

We experimented with different ways to display lexical scope and function application, including

- drawing lines between declaration and use

- highlighting each variable in a unique colour

- using nesting to show lexical regions

- allowing direct manipulation of data and inferring a list of plausible abstract operations

Again, we presented each of these to a small number of non-programmers, demonstrated writing a program, let them play around with the UI, and then asked them to explain the flow of the data through the program. None of the experiments led to much success. Since most of our testees can quite happily build complex systems in Excel, we suspect the culprit is one of control flow, data structures or variable binding.

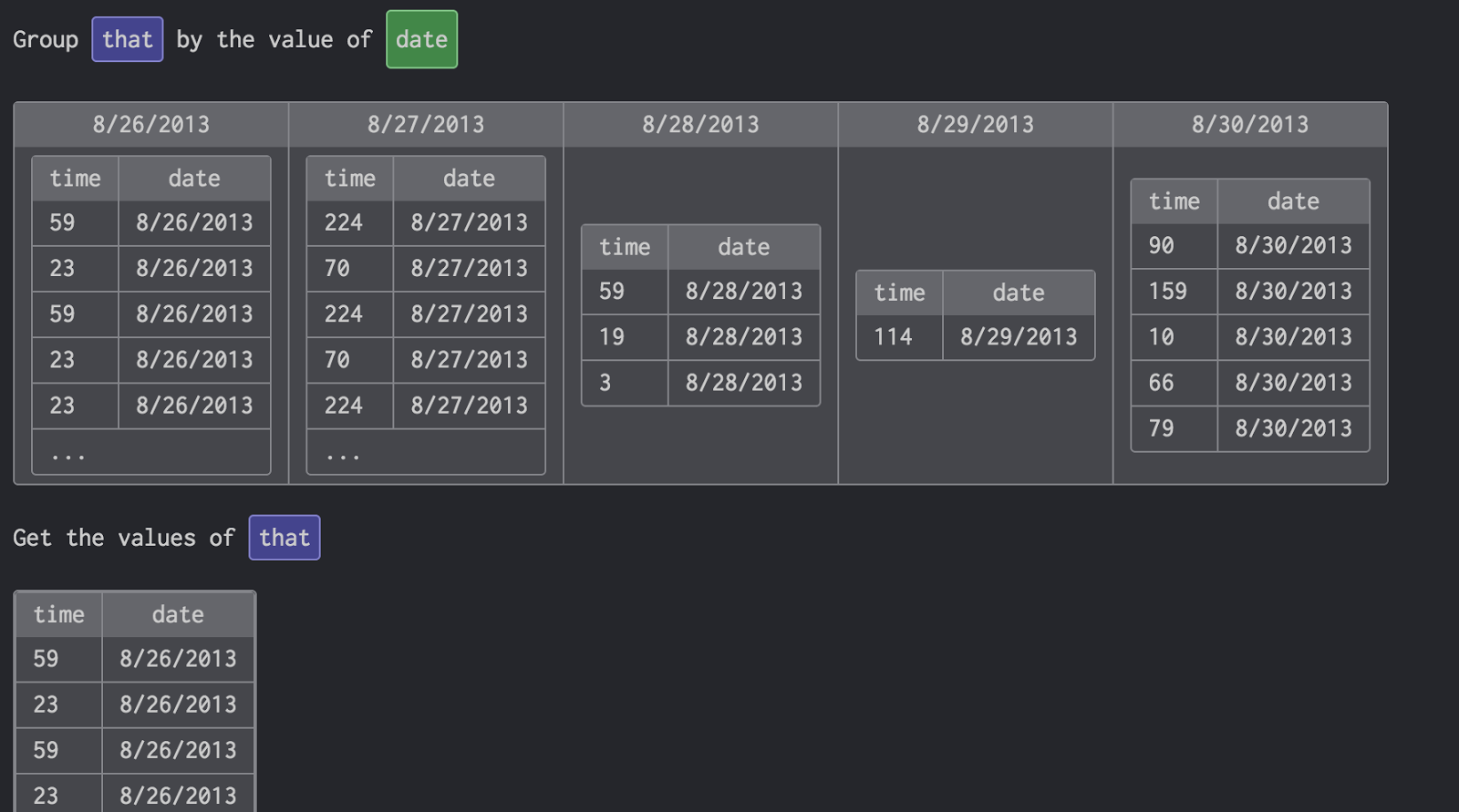

We replaced all the clojure data-structures (vectors, maps, sets) with tables - indexed multi-sets that were displayed as an Excel-like grid. Setting columns as unique keys allowed imitating the semantics of vectors, maps, sets and multi-sets while still having the same interface. This interface was more familiar to non-programmers and unique keys were more easily understood than having the same operations behave differently on different data-structures.

We also replaced the interpreter with a compiler, for reasons that are now unclear. Perhaps the editor was too slow when running user tests?

March

Our main data-structure was now a tree of tables. Rather than one big top-level function, we switched to a pipeline of functions. Each function pulled data out of the global store using a datalog query, ran some computation and wrote data back. Having less nesting reduced the impact of lexical scope and cursor passing. Using datalog allowed normalising the data store, avoiding all the issues that came from hierarchical models.

At this point we realised we weren’t building a functional language anymore. Most of the programs were just datalog queries on normalised tables with a little scalar computation in the middle. We were familiar with Bloom and realised that it fit our needs much better than the functional pidgin we had built so far - no lexical scoping, no data-structures, no explicit ordering. In late March we began work on a Bloom interpreter.

April

At the beginning of April our fledgling Bloom interpreter managed to stratify it’s own stratifier. Chris started working on a new editor designed around queries. In the meantime we wrote test programs using a pile of clojure macros. We were hedging our bets with respect to normalisation so the interpreter allowed arbitrary clojure data-structures as values and supported pattern-matching and calling clojure functions.

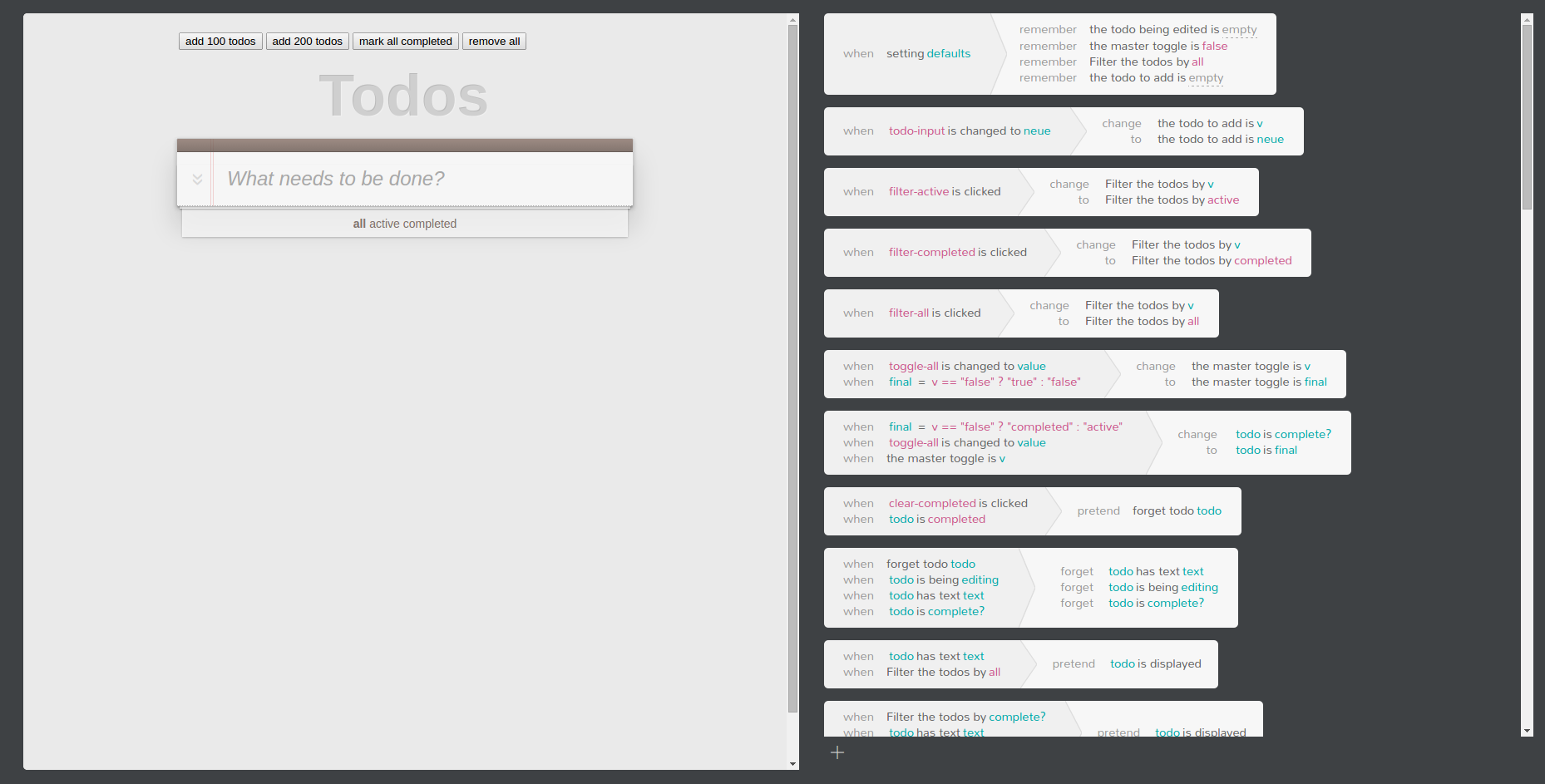

We added a simple UI library that watched the DOM table and rebuilt the entire UI on each tick and then began to build our first useful programs. I remember being surprised at how far we could get with a language that didn’t even support aggregation yet:

- dependency tracking, cycle detection and stratification ~ 50 loc, 13 rules

- todomvc (minus routing) ~ 140 loc, 30 rules

The editor developed enough that we could use it to build todomvc (which took around ten minutes to write) and live update todomvc as rules were edited. Rules were written in an If-This-Then-That style which went down somewhat better than the computation oriented interface we had before.

Interestingly, since the rules read almost like English, we started getting complaints that they were ungrammatical. Rules like ‘if [time = T] do …’ were met with the objection that there is always a current time and it’s not a matter of ‘if’. I suspect many natural language interfaces run into the same uncanny valley problem.

The interpreter was still painfully slow though. Complex interactions like autocomplete in the editor had delays on the order of seconds. We eked out some improvements by forking clojurescripts transient maps and removing all the features we didn’t use but it was clear that making the editor usable would require a much more sophisticated runtime.

May

Most databases use the model pioneered by System R. The query optimiser generates a variety of plans that could answer the query and chooses the plan with the lowest estimated cost. Each plan consist of a tree of operators (eg index lookup, hashjoin, mergesort). Each operator produces an iterable stream of results which is consumed by it’s parent in the tree. The leaves of the tree read from indexes or tables and the root of the tree produces the result of the query. This is a solid design and has been proven over and over. It’s also a mountain of work to implement. We weren’t feeling mountainous.

Luckily, we stumbled across a paper that details a much easier option: Leapfrog Triejoin: A Simple, Worst-Case Optimal Join Algorithm. Triejoin is a simple and efficient algorithm that can compute an entire datalog query in one pass.

Jamie got started on a btree implementation. Ironically, given our stated principles, the early effort was marred by a lack of observability and poor test coverage. After spending far too many days on debugging, the combination of a ascii-diagram printer and a series of double-check tests won through.

Jamie and Chris then worked independently on separate implementations of triejoin to reduce the odds of missing an important optimisation. Again, initial flailing was countered by printing simple ascii diagrams of the join process and writing yet more double-check tests. If there was anything we learned from this month, it’s that property-based testing provides massive leverage when writing complex code.

June

We had a few problems with triejoin: The paper mentioned that the choice of variable ordering was really important but put it off to a subsequent paper. For tables with lots of columns we ended up building large numbers of indexes to cover all the different query orders. Updating those indexes was getting expensive. The algorithm was patented (as was the incremental version) and we didn’t want to stand on a rug that might later be pulled out from underneath us.

We went through several different implementations of triejoin and triejoin-like algorithms, exploring the design space, and eventually hit upon the sudden realisation that the fundamental idea in triejoin is just constraint propagation. Using constraint solvers to implement query langauges is not a new idea and we are not the first to notice that this applies to triejoin but the idea hasn’t received much attention thanks to the dominance of System R designs. We built a basic propagator-based constraint solver (based on gecode) which, like triejoin, can calculate an entire datalog query in one pass, is reasonably fast and is substantially easier to implement than a traditional query plan optimiser.

All of our previous demos were rebuilt on top of the new system. TodoMVC and autocomplete were both reacting and re-rendering in sub-100ms. The editor was smooth enough to be usable. We even demoed to Andreessen Horowitz without anything breaking.

We still didn’t have incremental evaluation though. Every new input caused the entire program to recalculate from scratch. We were doing that fast enough that we could get away with it for small demos but it was clearly going to be a problem.

July

We knew the problem we needed to solve: incremental evaluation of recursive datalog rules under addition and deletion of facts. We just couldn’t find a solution.

Storing the entire provenance graph explicitly is too expensive. Semi-naive evaluation doesn’t handle deletions. DRED is known to often be slower than non-incremental evaluation for recursive views. Many papers that claimed novel algorithms were just variations on DRED. Higher-order delta processing ends up with exponentially many terms when a single transaction might change all views. Incremental triejoin is patented, and would also require solving our triejoin-related problems.

We circled around the problem all month, reading papers and sketching out ideas. Other work got done but we knew this was a problem that could sink the entire approach and so we kept getting drawn back to it.

Unlike the constraint solver, there was no sudden revelation. We got there by chipping away the problem space until we arrived at a more useful way of thinking about the problem. We had been locked into thinking that the only information available is the structure of the rule being evaluated and the sequence of decisions recorded from previous evaluations. Semi-naive evaluation uses the former to rule out cases where old inputs do not need to be considered. Incremental triejoin uses the latter to remember where it made decisions that may need to be changed.

Just as we saw a constraint solver by looking at triejoin from the right angle, we spotted a different way of thinking about incremental triejoin. Rather than directly recording sequences of decisions and replaying them, as triejoin does, we changed the job of the constraint solver.

The constraint solver operates by iteratively tightening the bounds on each variable in the query. Each tightening of the bounds rules out an entire volume in the solution space, effectively proving that none of the points in that volume can possible be solutions to the query. We now make the constraint solver responsible not just for finding solutions but for finding all of these proofs.

The end result of running the constraint solver is then a data-structure that encodes both why-provenance and why-not-provenance i.e. for every point in the solution space it can either a) tell you that the point is a valid solution and give you a list of which facts the solution depends on or b) give you one or more proofs that this point is not a valid solution. When facts are added to or deleted from a table, some of the proofs made by the corresponding constraint may be invalidated. When the solver is rerun, the provenance constrains the solver to only consider areas which do not have a valid proof.

From this point of view, semi-naive evaluation is similar to a provenance structure which doesn’t store any details of the proof and so has to invalidate if any matching table changes. The sensitivity index in incremental triejoin is effectively indexing the proofs by the changes which would invalidate them and then throwing away the original proof information. The examples in their patent show redundant sensitivity information being stored after facts are deleted - we should be able to avoid this because on deletion the new, simpler proof will overwrite the old detailed proofs.

How to efficiently maintain and query the provenance is still an open question. The proof for an entire volume can be encoded simply as the index of the constraint which tightened that bound. Likely some form of space-dividing tree (eg a k-d-b tree) could be used to store and query these volumes. (If we ordered variables like triejoin does then a single interval tree would suffice but then we would be back to having to choose efficient orderings). The usual concerns with overlapping volumes in high dimensional data-structures should be less of a problem here - we only need to cover the space so we can freely split volumes and throw away overlaps.

Thinking of provenance this way gives us a lot of flexibility to trade off storage costs against future re-evaluation costs. That flexibility, and the fact that it can mimic other solutions, gives me confidence that it is a useful way of thinking about the problem even though we don’t yet have an efficient implementation.

August

Since we needed to rebuild the runtime from scratch to accommodate provenance we took the opportunity to start porting all our code from clojurescript to javascript. The core clojurescript libraries were all too slow and allocation-heavy to use in a language runtime. We were suffering from long compile times and poor error messages (“Cannot call method undefined of undefined”) without being able to take advantage of any the benefits of clojurescript. Moving to javascript made writing low-level code much easier.

Implementing the provenance turned out to be really tricky. We went through various iterations, dealing with problems of representing proofs and reasoning about overlap between volumes and open/closed edges. We stored proofs in a single big array and focused on getting the logic right first.

Property-based testing was again essential. We initally used jsverify for testing but it had a tendency to fall over on large tests, like all the other javascript quickcheck ports. We ended up writing a library called bigcheck, which supports the basic quickcheck features but sacrifices bind for better performance.

The constraint solver stores information about each variable in the query in the form of lower and upper bounds on its possible values. The first totally working version of provenance required changing the constraint solver to use inclusive lower bounds and exclusive higher bounds to ensure that the resulting proof volumes all tiled nicely. A few weeks later this caused problems with function constraints because we had no way to indicate that a variable was completely determined. We ended up having to go and switch everything back to inclusive bounds on both sides and store more complicated volumes in the provenance. We eventually got all the logic working and validated the idea, but the naive implementation was far too slow to be useful.

September

At this point we had spent more than two months on incremental evaluation and we didn’t yet have a practical, performant implementation. We decided to put it aside for now and focus on writing programs in Eve. We exposed a stable interface for the runtime and compiler to allow writing interesting-sized Eve programs without constant code churn. The complex data-structures for tables, indexes and provenance were replaced with simple dummy implementations using arrays and sequential scans to reduce the odds of running into runtime bugs whilst writing Eve programs. Any new language feature we needed was implemented in the simplest way possible with little consideration for performance.

Surprisingly, the dummy runtime was still reasonably fast and we were able to bootstrap much of the editor and part of the compiler without performance problems. In hindsight, it’s not surprising that simple cache-friendly array scans outperform complex data-structures, given the small size of the demo programs we are working on and the divide-and-conquer nature of the solver.

We also encountered the Edelweiss model of time/change around this point and decided to run with it for a while. The main appeal is that it brings us back to the Out Of The Tarpit way of thinking, where the only real state is the input log and everything else is just a view over the inputs. Of course, storing every input forever is impractical. Rather than manually aggregating or forgetting inputs as Mosely suggests, Edelweiss uses static analysis of datalog code to figure out when an input can no longer affect the state and can be safely garbage collected.

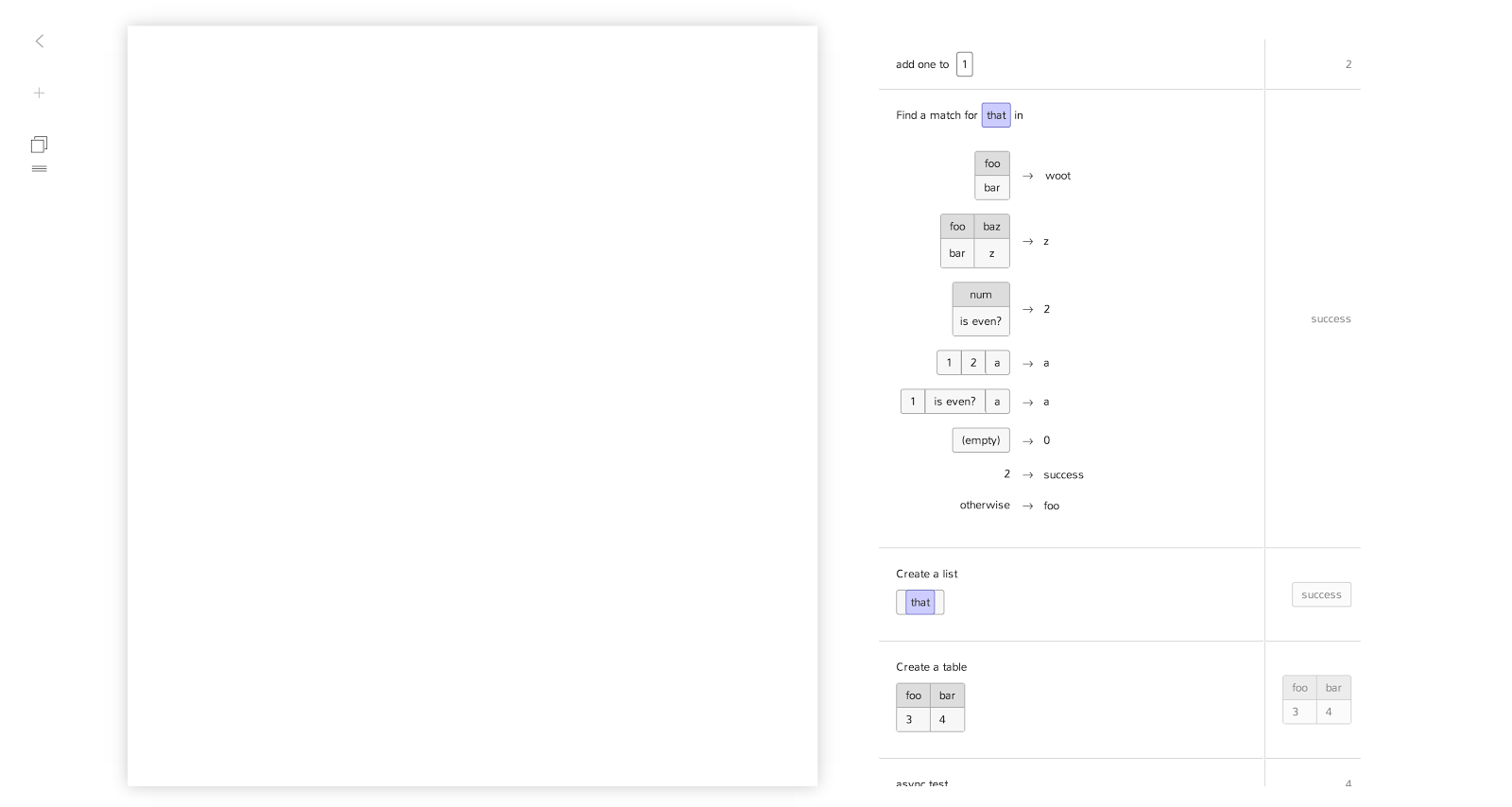

The editor moved from a fill-in-the-blanks textual representation to a more Excel-like representation. Showing the intermediate data and interacting with it directly seems to be easier for most people than dealing with variables. There is no loss of power compared to the previous editor but it is much less dense. It works for editing code but we will have to find some more compact representation for when users are browsing code.

Today

This brings us more or less to the present. Interface aside, the current language is essentially a classic datalog with stratified negation and aggregates. Table fields can contain any scalar js value and queries can call any pure js function.

The state of the system is persistent and updates return a new system. Data is stored in individual tables which expose constraint propagators and equality/diff operations. Rules are connected by a pull-based dataflow with dirty tracking.

Each rule is implemented by a constraint solver which supports table constraints, negation constraints, function constraints and constants. Provenance information is collected but currently ignored - solvers have to recalculate the whole space on each run.

Aggregates are implemented as separate dataflow nodes. Like the solver, they have enough information to be implemented incrementally but currently they just recalculate on each run.

The editor and small parts of the compiler are built with a javascript dsl that inserts data into code tables. Systems can recompile themselves on the fly when their code changes. There is space to support data migrations alongside code changes but we haven’t needed it yet.

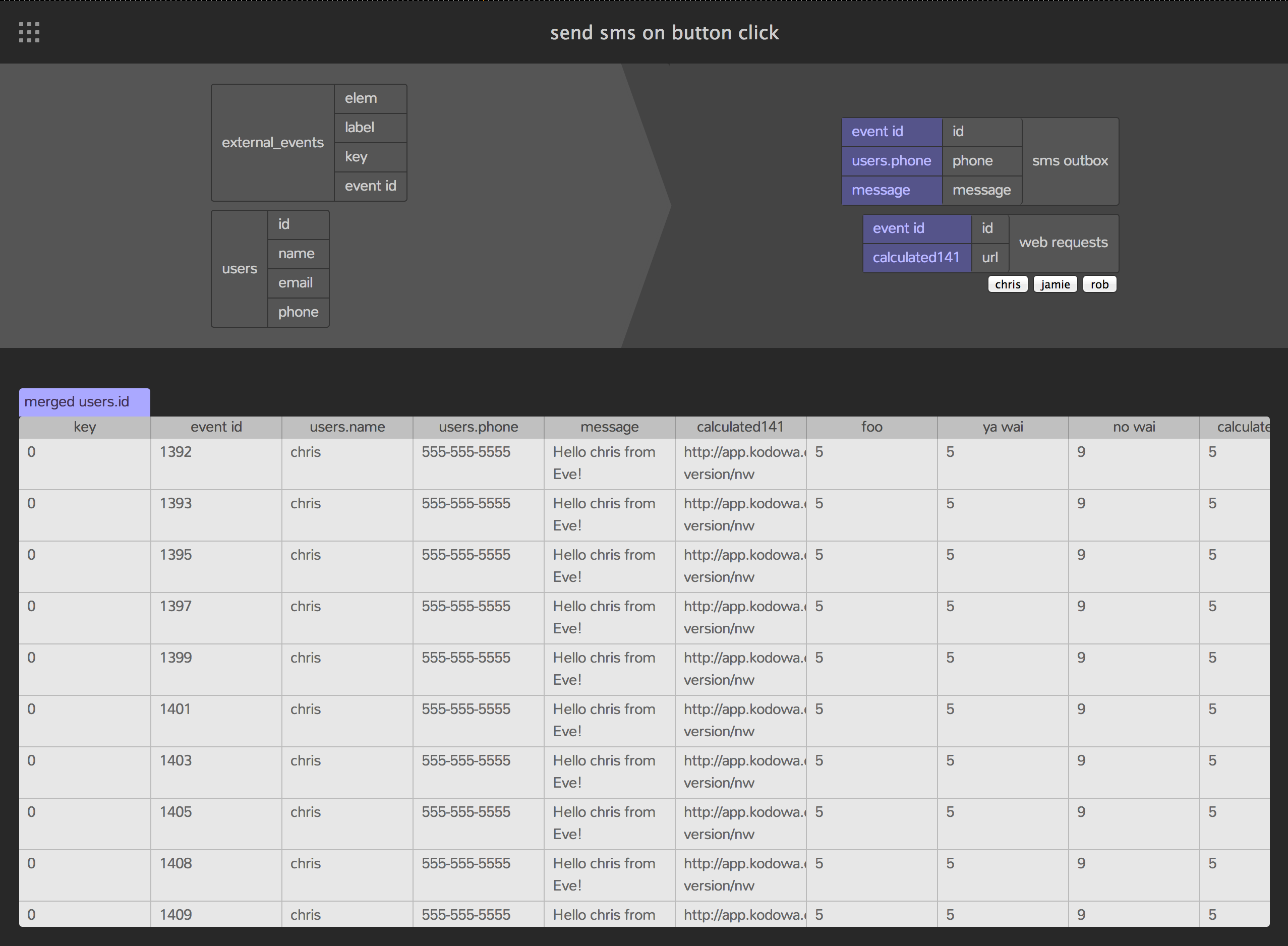

The UI library is similar to React. Rules define UI elements by inserting data into the UI tables. An external watcher uses the table diffs to update the DOM after every transaction. UI callbacks simply insert data into input tables.

The editor can show tables and edit rules, has basic debugging support and can compile itself. It is surprisingly fast given the simple implementation - 20-40ms to react and rerender in response to button clicks. However the lack of incremental evaluation and garbage collection causes it to fall over after a few minutes of text entry.

Keeping the implementation small and simple is essential given the size of our team. So far we have around 3.5kloc of javascript, which breaks down as:

- runtime - 800 loc

- compiler - 150 loc

- js dsl - 300 loc

- ui/io libs - 450 loc

- ide - 1000 loc

- bigcheck - 200 loc

- tests and benchmarks - 500 loc

Now that we have a passably fast and stable language to work with, the main focus over the next month or two will be on improving the programming experience.