Dev Diary (Dec): more zzjoin, communication, process spawning

Jamie Brandon - 08 Jan 2015

Yet more turkey was had. What did they ever do to us?

Indexes and joins

We continued work on the zzjoin idea from the end of last month. The current version is competitive with pairwise hashjoins on many workloads but performs poorly on highly skewed inputs. In Skew Strikes Back the authors argue that pairwise join algorithms cannot be optimal on many problems and that their key weakness is an inability to deal with certain kinds of skew.

For our current algorithm, a simple example is the query select from A, B, C where A.y = B.y and B.z = C.z where A and B are large but C only has one row. The current version propagates whenever it can, so it will always choose to reduce the solution space to match the one row in C. If that row has a high skew (ie it joins with a large number of rows in B) then this can cause a lot of work, work that we might not have to do if we can easily determine that the join between A and B is empty. Traditional query compilers deal with this by estimating the size of the joins ahead of time and choosing an appropriate order to evaluate them in.

In Skew Strikes Back the authors give a harder example: select from A, B, C where A.y = B.y and B.z = C.z and C.x = A.x where each of A, B and C has some rows with high skew. Any pairwise join produces O(n^2) intermediate results but the query itself only has O(n) results. The only way to deal with this is to make use of all the tables at once and to use different join orders for different subsets of data to navigate around the high skew.

The new version we are working on controls propagation much more carefully. At each step, it chooses one variable and propagates the next bit of that variable. The choice of variable is determined by some heuristic, the most obvious being the total number of index nodes needed to track the resulting space - a measure that is closely related to skew. Instead of performing cost estimation up front and picking a static join order, like tradition query compilers, we effectively perform cost estimation during execution and use that to decide which part of the join to explore next. This allows us to detect skew and to choose different join orders for different subsets of the data to compensate. It also greatly reduces the amount of constant time work we have to perform per step.

A few days ago we came across Joins via Geometric Resolutions which develops a similar join algorithm called tetris and proves a number of beyond-worst-case results for it. Both tetris and zzjoin represent the solution space as an n-dimensional volume and attempt to tile the space with empty volumes from the indexes, represented as tuples of bitstrings. Where zzjoin uses a strict binary decomposition of the space and focuses on choosing a good decomposition, tetris uses a complex indexing and memoization scheme to exactly represent their tiling. While the similarity is encouraging, the authors argue that this memoization scheme is essential for achieving their strong theoretical guarantees. We need to do more work to figure out how that affects our ideas.

Communication

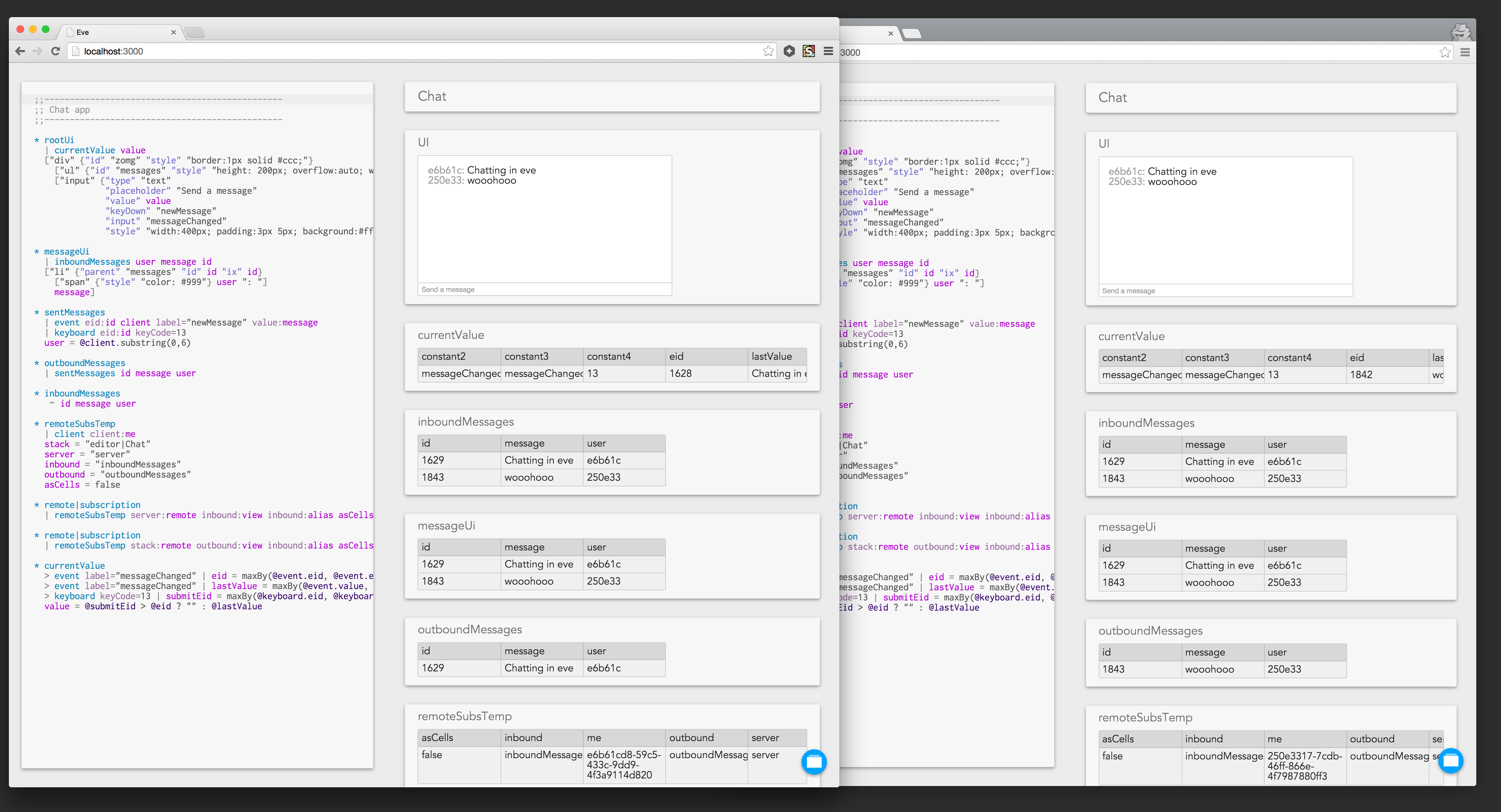

Eve processes can now communicate with each other. Unlike Bloom we don’t have a special message table for communication. Instead, processes can dynamically subscribe to views in other processes, creating a local copy which is asynchronously updated. Compared to direct messaging, this allows observation without cooperation and enables easier composition of processes.

Under the hood, it’s still just plain old messaging and doesn’t attempt to hide the realities of distributed communication. The subscriber sends a subscription request and the remote process sends back timestamped diffs continuously until the connection is broken. It’s not yet clear exactly what consistency guarantees we will provide for eg multiple subscriptions to different views in the same process. We will have a better idea once we build more distributed programs and see what kind of patterns emerge.

Spawning

Eve processes can now spawn subprocesses and inject code into them. Together with the new communication API this allowed much of the IDE architecture to be lifted into Eve. When running in the browser only the UI manager lives on the main thread - the editor, the compiler and the user’s program all live in separate web-workers. The editor uses the process API to spawn both the compiler and the user’s program and then subscribes to the views it needs for the debugging interface. Both the editor and the user’s program send graphics data to the UI manager and receiving UI events in return.