Eve Dev Diary (March 2016 Part 2: Platform)

Corey Montella - 22 Jun 2016

Platform

For the platform, our main goal for March was to get a server running and everyone in the office connected to it and coding via a REPL. Over the course of a couple months we transitioned from a traditional row/tuple/table store model to storing (Entity, Attribute, Value) triples called EAVs. To support additional features of the language, we expanded this triple to include additional parameters: Bag, Tick, and User. So the full specification for a fact is now (Entity, Attribute, Value, Bag, Tick, User).

- Bag - This allows you to compose arbitrary datasets, and provides a mechanism to control visibility of facts. You might put all your facts about planets and astronomers into one bag, while your quarterly earnings report goes into a different bag. Bags will help us with features like version control and distribution. For example, the logic for a networked game like chess might be held in one bag. Then a specific instance of the game would include the game logic bag, as well as additional state facts. Then each player would have their own personal bags representing their local game state, which is coordinated to the other player through the instance bag.

- Tick - The time when the fact was created. This allows a partial ordering of the facts. I will have a lot more to say about this in a future post, but this enables some exciting features like time-travel debugging, what-if scenarios, and very low-cost, strong consistency.

- User - The ID of the user who created the fact. This would allow you to query or exclude all facts added to Eve by a particular user, for instance. Or it can be used to figure out who added a particular fact to the database. This will also help for things like permissions, where you can restrict access to edit/view certain facts. For example, you don’t want your employees to set their own salaries or see anyone else’s.

Server

Cardwiki and WikiEve used an old runtime written in TypeScript that relied on the client’s localStorage to hold the database. Setup was easy for the user, but without a server we couldn’t easily support features like distribution, redundancy, or collaboration. Since Eric started in December, he had been working on a new runtime, (ClojEve, written in Clojure), as the rest of us worked on WikiEve. By April we were ready to migrate to this new environment, which means we needed a protocol. We landed on a JSON interface with four message types: query, error, result, and close.

query:

{

type: "query"

id: id

query: query

}

close

{

type: "close"

id: id

}

The client can send two types of messages: a query or a close. Each query has a UUID. This is sent to the server along with a plain text query written in our query syntax (more on that in the next section). Any query sent to the server remains open indefinitely, until the client sends a close message with the corresponding ID.

result:

{

type: "result"

id: id

adds: fact[]

removes: fact[]

}

error:

{

type: "error"

id: id

reason: reason

}

When the server first receives a query, it sends back a result message. This message is contains the ID of the associated query, along with any additions or removals from the results. The initial result will only have adds, since it is computed from scratch. But if the query remains open, adds and removes are sent incrementally as the database mutates.

Syntax and Compiler

Last month, we re-introduced a syntax for Eve for the first time since 2014. The syntax was an s-expression style syntax, intended for internal use only. In general, we were happy with this because it allowed us to easily translate tree-like structures to the syntax. For instance, this property made builing the NL interface easier. This month, we made some changes to the syntax to make it easier to write. We removed the project! statement, replacing it with a bracket syntax. Further, we removed the select statement, and replaced it with fact, which can act like multiple selects at once. For example, this

(query

(select "eavs" :entity "apple" :attribute "color" :value color)

(select "eavs" :entity "apple" :attribute "tag" :value tag)

(project! :color color :tag tag))

becomes

(query [color tag]

(fact "apple" :color :tag))

Which is much simpler. This compiles using a two-stage process. We first parse the original input and translate that to an intermediate language (IL), which decomposes the query into a more primitive form. The above query compiles to the following IL:

(query [color tag]

(fact-btu :entity "apple" :attribute "color" :value color)

(fact-btu :entity "apple" :attribute "tag" :value tag))

Here, the fact statement has decomposed into two fact-btu statements, which resemble the select statement of the previous syntax. IL code then goes through another level of translation into Eve bytecode. The above IL code translates into the following bytecode:

((bind

main

((tuple [3] [0] [1] * nil) (send "query2725||color,tag" [3])))

(bind

"query2725||color,tag"

((scan [3] [])

(delta-e [4] [3])

(= [3] [4 0] "apple")

(filter [3]) (= [3] [4 1] "color")

(filter [3]) (scan [3] [])

(delta-e [5] [3])

(= [3] [5 0] "apple")

(filter [3])

(= [3] [5 1] "tag")

(filter [3])

(tuple [3] [0] [1] [2 2] nil [4 2] [5 2])

(send "query2725||color,tag-cont" [3])))

(bind

"query2725||color,tag-cont"

((delta-c [4] [5])

(tuple [3] [0] [1] [4] [5])

(send out [3]))))

Finally, the above code is sent to the executor, which executes the code and returns a result. In the context of the client-server architecture, the result is packaged as an incremental add/remove message, which is sent to all clients listening to that query. If the executor encounters an error while running the query, an error message is created, indicating what the error was, and where in the source the error occurred.

The IL and bytecode translations for each query are passed to the sender in an “info” message. This message contains metadata meant to enable interesting interactions for editors. For example, we can add the whole parse tree to this message, and then a client editor can use the tree to style code.

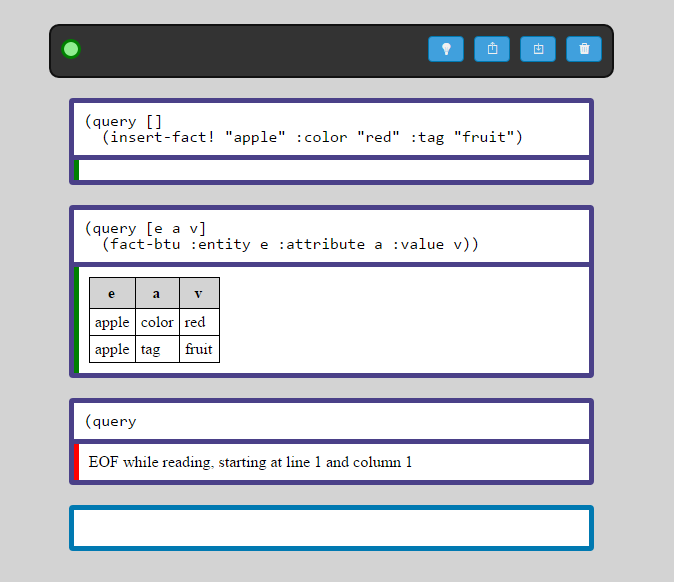

REPL (github)

Putting it all together, we started building a REPL. A basic REPL for Eve is actually very simple, given the protocol laid out above. When you start the REPL, it opens a websocket connection to an Eve server. Then you can type a query in a textbox and send it to the server. The REPL forms a message according to the query protocol and waits for a response from the server. When a response is received, the REPL displays it according to its type. Result messages are rendered as a table, while error messages are rendered as text.

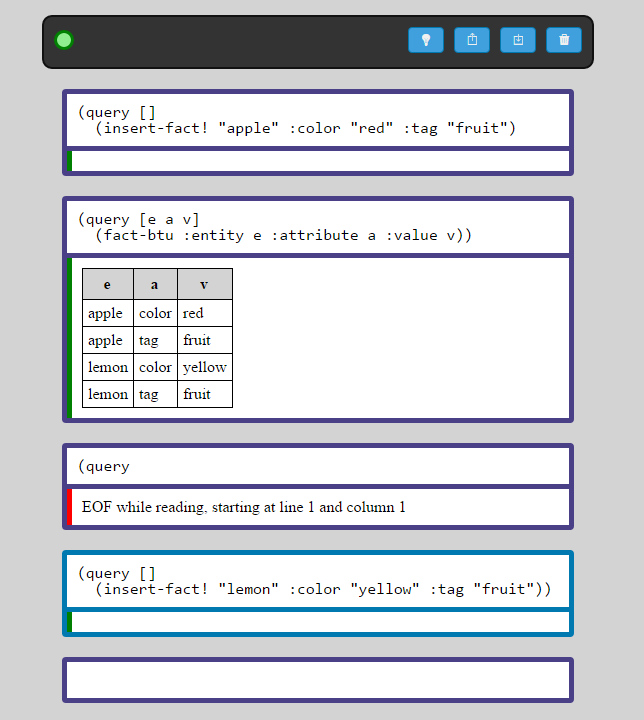

In this example REPL session, the user added some new facts about apples in the first card. In the second card, the user asked for all EAV facts in the system, which are displayed in a table. The final query is malformed, so Eve returned an error message.

But since this isn’t an ordinary REPL for an ordinary language, we have some nice behaviors. Queries are left open by default, so they continuously receive updates from the server as they become available. So if another Eve user adds a fact that affects any of your open queries, you’ll see that change immediately.

Here, the user added new facts about lemons, which are added to the result table in the second query.

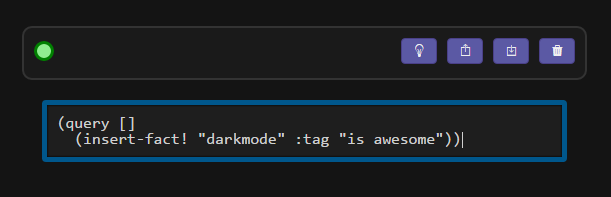

Other features include the ability to save/load REPL workspaces to/from a file, automatic reconnect if the server dies, and the ability to export result tables as CSV files. And of course, dark mode!