Dev Diary (August 2016)

Corey Montella - 31 Aug 2016

This post has been updated. See the original here

(Eve is a new programming language, and this is our development blog. If you’re new to Eve, start here)

The majority of August was spent adding language features, fixing bugs, writing documentation, and listening/responding to community feedback. We did a lot this month, so this update is going to be a long one.

Platform

The Eve platform saw rapid improvements over the last month as we quickly responded to user feedback. As is the case when all projects are set loose in the wild, we encountered stability, performance, and usability concerns almost immediately. Let’s take a look at all of the work put into the Eve platform first.

Word Choice Adjustments

Surprisingly, one of the most difficult aspects of developing a language is deciding on the words and verbiage used to describe Eve concepts. Choosing the wrong words can alienate users and make things more confusing than they need to be. Therefore, we’ve spent countless hours looking through thesauruses and dictionaries for the perfect words. In presenting the language to new users, we’ve learned some of the choices that made sense to us didn’t make sense to others. For instance, we used to talk about “freezing”, but community feedback suggested that word didn’t provide an intuition for how that command actually worked.

For anyone following our development, but not following the Syntax RFC discussion, we’ve made the following adjustments to how we talk about Eve:

freeze -> commit

maintain -> bind

object -> record

bag -> database

New Function Syntax

Whereas most languages use functions to accomplish code-reuse, Eve takes a different route; our records obviate the need for most functions. Therefore, we don’t fully support user defined functions at the moment. Nonetheless, functions are useful for primitive operations, like math or string manipulation. Thus, we adjusted our function syntax to look a little more like the record syntax.

Let’s look at the sine function:

y = sin[degrees: 90]

The first thing to notice are the square brackets. These are reminiscent of the record syntax, which also uses square brackets. That’s because a function call is really just sugar for:

[@sin #function degrees: 90 value]

which is a record like any other. The new function syntax uses the value attribute as an

implicit return, so functions can be inlined into expressions.

The second thing to notice is that arguments are explicitly defined at the call site. This has several nice properties. First, it makes code more readable and self-documenting; any reader of the program unfamiliar with the function arguments can read them where the function is called, without having to look up documentation. Second, explicit arguments allow a nice mechanism to provide alternative arguments. For instance, we could use the sine function with a radian input:

y = sin[radians: angle]

The reader of this program doesn’t need to guess if the input is radians or degrees. One interesting thing you can do with this is add custom arguments to existing functions. In this example, we create a new coordinate system that takes angles in “fun-degrees”:

match

return = sin[angle: value? / 2 + 30]

bind

sin[fun-degrees: value?, return]

And then we can use the new argument the same way we use the default arguments:

match

answer = sin[fun-degrees: 40]

bind

[#div text: answer]

Finally, this syntax allows for optional arguments. For instance, in the case of count, the per argument is optional. So we can use count in the following ways:

y = count[given: students]

y = count[given: students, per: grade]

Databases

We’ve started thinking more about how modularity will work in Eve. For a while now, we’ve had a concept of “databases” (formerly bags), which are just containers of facts. So far, we’ve only exposed two databases: a default “session” database and a “global” database. The global database was exposed to users via commit global, which directed committed records to a global database accessible by any session on the server.

In the modularity branch, we’ve opened up the ability to send facts to and select facts from specific databases. For instance, until now a committed #div was implicitly directed to a special browser database. Now, if you want to render something in the browser you’ll have to tell Eve to put it there explicitly:

commit @browser

[#div text: "some text"]

Databases are specified after one of the three actions: match, commit, or bind. If no database is specified, the database is implicitly a default session database. You can even work with multiple databases at once:

match (@my-database, @your-database)

[#person name]

bind

[#div text: ]

This would select every #person from two different databases, essentially merging two databases.

With this mechanism in place, we can start to talk about how modularity and libraries will work in Eve. For instance, I could create a custom math library, and what I would distribute is a database. Then anyone who wants to use my custom math would do the following:

match @custom-math-lib

...

We still have a lot of work to do here, so this feature is not available on the master branch yet. Stay tuned for an RFC coming next month on modularity.

Talking with the outside world

Eve cannot thrive in isolation, so we need a way to communicate with the outside world. We’ve done some work on this front, adding the ability to read/write files, handle JSON (opening up the ability to interact with any JSON compatible API), and handle HTTP requests. This work is available in the process branch.

What’s nice about our solution here is that interacting with the outside world doesn’t look or feel any different than interacting exclusively within Eve; you still match and modify records, except the facts in those records originate from external sources. If you’ve been using Eve, then you’re already interacting with the browser through changing the DOM and handling events like clicks and keypresses.

Eric has been working on a little HTTP file server written in Eve. It’s still a work in progress, but the functionality to accept requests and serve files is already in place. Take a look at how an HTTP request is handled:

Start path resolution

match

r = [#http-request]

split[text: r.request.url, token, index, by: "/"]

fr = [#root]

bind

[#path index: 1, file: fr]

[#path index token]

Resolve a path

match

[#path index: pindex, file: pfile]

f = pfile.child

child = [#path index: (pindex + 1), token: f.name]

bind

child.file := f

After some more work to determine the requested file is available, then we can send a response:

match

r = [#request-object extension file connection]

ct = [#content-type suffix: extension]

commit

connection.response := [

content: file.contents

status: "200"

reason: "OK"

header: [Content-Type:ct.type]]

r := none

bind

r.completed := true

You’ll see here that we are interacting with both an external #http-request, and the file system through #path. Again, what’s notable is that despite interacting with data external to Eve, the code is written as if you were working entirely within the boundaries of Eve. You can check out the full program to see the rest of the implementation details.

Syntax Highlighting

We added syntax highlighting to the built-in editor!

Eve and Markdown

One key feature of the Eve programming model is that the order of statements doesn’t matter. A nice implication of this property is that we can write Eve code in an order that makes sense for a human, as opposed to writing code in an order that is imposed by the compiler or runtime. This idea is the basis for literate programming, a practice for writing programs introduced by Donald Knuth in 1981. The idea behind literate programming is to treat a program as a document of prose written to a human audience, with code interspersed throughout. In writing this way, a programmer can use prose and formal methods to reinforce one another, leading to programs that are (in principle) easier to maintain. We talk about some of the benefits of literate programming here.

Whereas other literate programming implementations require a “tangle” step to turn a literate program into a compilable program, Eve’s semantics mean a *.eve file can be rendered as markdown or executed by Eve without any additional compilation steps. We accomplish this by being CommonMark compatible; Eve programs are written just as you would write any markdown document, but code blocks containing Eve code are actually executable.

We’ve written a few literate programs this way. If you follow our blog, you’ve already seen some of them:

Each of these blog posts are executable Eve programs “as-is”; just send them through the Eve compiler and they’ll run. As Eve grows, we hope more people will join us in practicing literate programming, but there’s nothing about Eve that demands writing code this way; you can write programs with as little or as much prose as you prefer.

Views

We’ve been thinking a lot about what kind of graphical tools would be useful for working with the textual version of Eve. One thing currently missing from Eve is the ability to explore the contents of the Eve DB. Without this ability, Eve is as opaque as any other programming language. After all, the ability to inspect your program as it executes is one of the core features of our language.

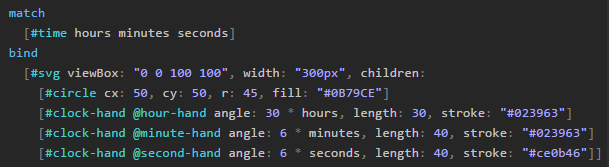

An idea we keep coming back to is the concept of “views”. Views are small graphical elements that represent records in the system. By default, they are just small squares, but a programmer can imbue them with properties (position, color, size, shape, etc.) to visualize the records they represent. For example, a graph can be constructed out of views by applying height and position properties to them, like in this example:

![]()

Here, we use #pixel (views used to be called pixels, so this would currently be accessed using #view) to inspect some records. Three views are displayed, one for each #clock-hand. In this case, since we’re inspecting records, the views display the attributes and values for each of the records. Then, we change to a different mode and look at the history of a specific attribute on #clock-hands, namely x2. This results in three graphs illustrating how x2 changes for each #clock-hand over time.

Obviously, this is just a concept at the moment, but the core idea we like about views is how flexible they are. We can package some default functionality, like the record inspector and history illustrated here. But even more importantly this functionality should be trivially extended by the programmer.

Community

I’m especially excited by the engagement we’ve seen from the community so far. It’s hard to know exactly how many people are following our development and using Eve, but so far we’ve received comments and feedback from users in Sydney, Copenhagen, Moscow, Finland, Hong Kong, the UK, Germany, and many other places.

Issues + Pull Requests

Thank you to everyone who submitted a PR or an issue report. Specifically, thank you to @btheado, @bertrandrustle, @RubenSandwich, @frankier, @dram, and @martinchooooooo. Let me know if I missed anyone!

RFCs

The syntax RFC received a lot of activity this month, surpassing 100 comments from over a dozen users. Your comments have been well thought out, provocative, and very constructive, so thank you to everyone who has participated so far. Due to the feedback we received, we’ve already made several adjustments to the syntax, including changes to keywords and the general vocabulary of Eve (see above).

Documentation

Documentation is still in an early stage, but it’s improving daily.

Syntax Quick Reference

We put together a short syntax reference with all the necessary details to help you write Eve programs.

Eve Handbook

The Eve Handbook has received some work this month, particularly in the area of documenting the standard library. If you’d like to contribute to the development of Eve, this is the easiest way to get started. You don’t even need to contribute any content; just pointing out the shortcomings of this document will help in its development. Major areas of improvement include:

- Completeness - are there any missing gaps?

- Accuracy - is the handbook true to Eve?

- Exposition - is the document written in an order that helps people learn the language?

- Examples - many examples are needed, especially for the standard library

We’ll be improving the handbook and other documentation daily, so keep checking back.