Eve Dev Diary (Oct): bootstrap editor, experiments, aggregates

Jamie Brandon - 05 Nov 2014

We spent most of October working on the language design rather than the implementation. We wrote lots of simple programs and ended up reworking some features that were awkward in practice. We also built a text-based editor to use while we bootstrap the full IDE.

Bootstrap editor

Up until now we were using a javascript dsl to write code in Eve. Feedback even in javascript is a little slow for our liking so we hooked up a simple editor that compiles and runs on every change. The total delay from key press to results is around 50ms, most of which is spent marshalling data to and from the webworker.

This has improved our productivity a lot. The plan now is to build on this editor incrementally, so that we can use new features immediately rather than having to wait until the entire IDE is bootstrapped.

Experiments

TodoMVC is an application that is simple to implement but makes use of all the features needed for complex client-side web applications. This makes it useful for comparing different approaches to client-side development.

We came up with a similar set of simple programs that characterise what we expect to be common use-cases for Eve. For this month we picked five examples to focus on:

- Recording, analysing and presenting data from a simple high-school physics experiment (data entry, calculation, presentation)

- Tracking time and generating invoices (reactive UI, calculation, presentation)

- Calculating compound interest over time (data entry, calculation, recursion)

- Reminding the user to bring an umbrella to work if the forecast is rainy (scheduling, async IO, parsing)

- Simulating a turing machine (completeness)

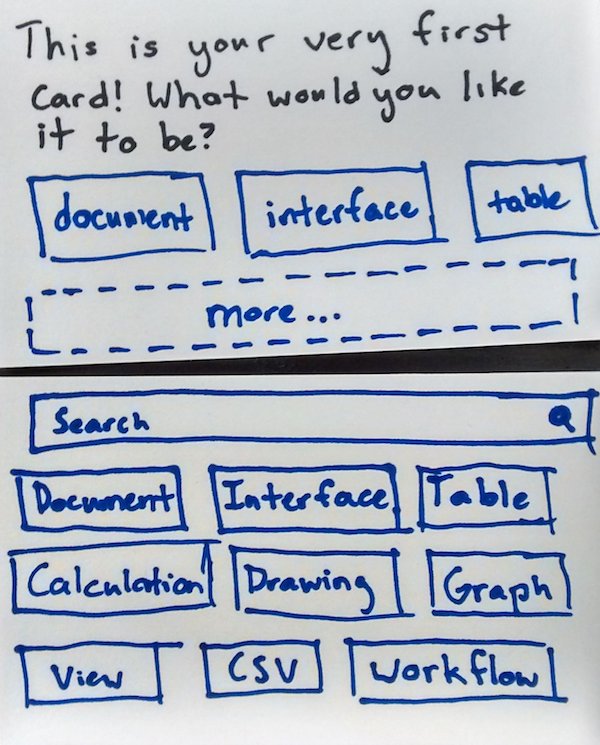

We ran through each of these and figured out how we as programmers would expect them to work. We then had Rob try to implement each program using our ‘mock UI’, which is just drawn by hand in real-time.

Actually trying to validate our design would require more formal testing with a wide range of users - this is just aimed at finding low-hanging mistakes or difficulties with little time investment. Rob doesn’t have Programmer Stockholm Syndrome yet and will flat out refuse to do things that seem to us like very reasonable workarounds.

The main problems we found through our experiments were related to position, mutation, context and aggregates.

Position

The compound interest example is usually written in excel by starting with the columns Year and Balance. The first row is filled in by hand, say with 2014 and $5. Then the year row is dragged down to produce a list of consecutive years. The second balance entry is filled in with a formula that directly references cells in the row above - = B0 * 1.01. Dragging down the balance column leads Excel to generalise this formula and apply it correctly for each cell.

The first problem here is the part where the formula references ‘the row above’. The semantic intent of the formula is bound up in the layout of the program. Tables in Eve don’t have an intrinsic order so the concept of ‘the row above’ doesn’t have any meaning. Despite that, the fact that we have to choose some ordering to display it leads people to want to use that ordering.

The proposed solution is to have operators that give the desired results but expand to existing primitives. So, for example, if the user is clicking on the row above and the table is currently sorted by Year, we could insert the formula [Balance] for [Year] before [CurrentYear] which (in pidgin SQL) expands to select Balance, Year from CompoundInterest where Year < CurrentYear sort by Year descending limit 1. This allows novice users to get the results they want while at the same time teaching them how to construct more complex queries.

Mutation

Where most languages express state as a series of changes (‘when I click this button add 1 to the counter’), Eve is built around views over input logs (‘the value of the counter is the number of button clicks in the log’). Thinking in terms of views makes the current language simple and powerful. It removes the need for explicit control flow, since views can be calculated in any order that is consistent with the dependency graph, and allows arbitrary composition of data without requiring the cooperation of the component that owns that data.

Whenever we have tried to introduce explicit change we immediately run into problems with ordering and composing those changes and we lose the ability to directly explain the state of the program without reference to data that no longer exists.

For some domains (eg accounting, analytics) thinking in terms of views seems to be easy and familiar for everyone we have talked to. For other domains, particularly UI, most people preferred to talk in terms of change to the current state. This leaves us with some open questions.

Firstly, to what extent is this learnable/teachable? Is it possible to make an interface where the Pit of Success naturally leads to seeing everything as views?

Secondly, is it possible to exploit the duality between the two models and flip back and forth between them. For simple examples like counting button clicks this is easy. It’s not obvious how it might work in general though.

Context

We ran into a number of problems that boiled down to tracking context:

- In UI code it’s often useful to be able to refer to the current user or to some set of state associated with the current user.

- In multi-page forms, the contents of the previous pages need to be stored and kept up-to-date as the user moves back and forth through the forms.

- In the physics experiment example, it is useful to be able to treat experiment parameters as constants when recording and analysing the first experiment and then handle future experiments by editing copies of the first program.

- When building UI components, to make the component reusable in multiple places the programmer needs to attach a component id of some sort to all of the state for the component.

In a traditional imperative language, this sort of context is provided by access to dynamic scoping (or global variables - the poor mans dynamic scope) or by function parameters. In purely functional languages it can only be provided by function parameters, which is a problem when a deeply buried function wants to access some high up data and it has to be manually threaded through the entire callstack.

In each case, there is some context identifier that needs to be threaded through all the code running that context and this feels like something that could be automated. We could perhaps have a way to assign a context to a set of views, so that each of those views is parameterised by a context id and can treat that context as if it is the only one that exists. That allows us to have flat, global tables for easy composability and debugging but still be able to look at code in a local view that ignores the context columns.

Aggregates

Classic datalog is often extended with query-level aggregates:

department("engineering")

department("business")

department("marketing")

worksIn("jamie", "engineering")

worksIn("chris", "engineering")

worksIn("rob", "business")

employeesPerDepartment(Department, count(Name)) :-

department(Department)

worksIn(Name, Department)

The body of employeesPerDepartment produces three rows:

Department, Name

"engineering", "jamie"

"engineering", "chris"

"business", "rob"

Then the results are grouped by the non-aggregated columns that are in the head (in this case just Department) producing:

employeesPerDepartment("engineering", 2)

employeesPerDepartment("business", 1)

We used the same model for Eve (although with more explicit control over grouping and support for sort/limit). The problem is that this code will not produce employeesPerDepartment("marketing", 0) because there were no rows to aggregate over at all. There is no way to distinguish between an empty aggregate and no result at all. If you actually want employeesPerDepartment("marketing", 0) you need to add another rule to handle empty departments:

employeesPerDepartment(Department, 0) :-

department(Department)

NOT worksIn(Name, Department)

This results in lots of duplication of code to handle each case.

SQL handles this by having left-joins insert nulls in rows which would otherwise be missing and by treating nulls specially in aggregates.

Department, Name

"engineering", "jamie"

"engineering", "chris"

"business", "rob"

"marketing", null

employeesPerDepartment("engineering", 2)

employeesPerDepartment("business", 1)

employeesPerDepartment("marketing", 0)

This adds complexity to the language and implementation and is often regarded as a mistake. Instead, we replaced query-level aggregates with clause-level aggregates:

employeesPerDepartment(Department, Count) :-

department(Department)

> worksIn(Department, _Name) | Count = count(Name)

The left-hand side of the clause returns all rows that match the specified variables and the right hand side reduces those rows into scalar values. The grouping on the left-hand side makes it explicit that we want to perform the aggregate per department. It’s easy to incrementally maintain these aggregates using map-reduce trees and they nicely handle temporal views such as:

user(Id, CurrentName, CurrentAddress) :-

registered(Id)

> nameChanged(Id, _Name, _Time) | CurrentName = lastBy(Time, Name)

> addressChanged(Id, _Address, _Time) | CurrentAddress = lastBy(Time, Address)

We still need to think more about how to handle multiple returns, argument passing and sort/limit with this strategy but the basic form is already working.