Eve Dev Diary (Nov): experiments, performance, integrity constraints, zztrees

Jamie Brandon - 01 Dec 2014

We are all so very full of turkey.

Light Table

We released Light Table 0.7.0 and gained three awesome committers who have decimated the bug count, moved all the infrastructure over to community control and changed to the MIT license.

We also have an experimental branch using atom-shell instead of node-webkit. This gives us smoother performance and useful new features like using iframes to isolate user code from the editor itself.

More experiments with Eve

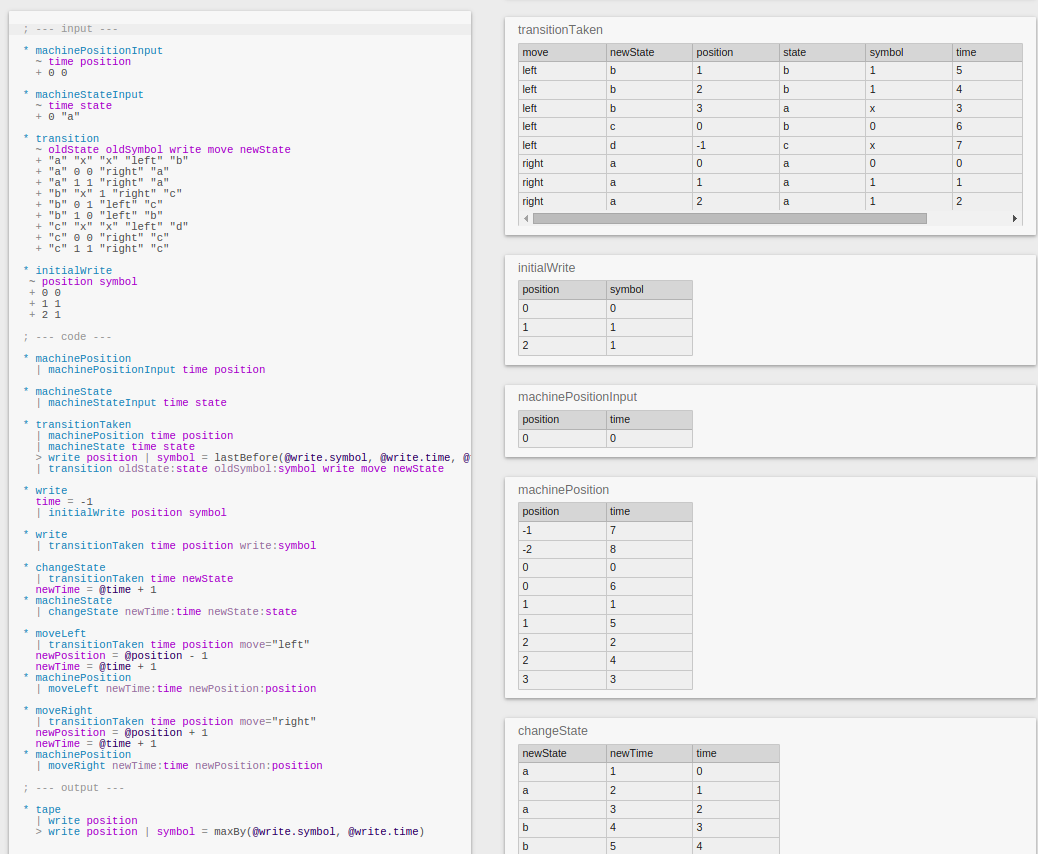

We built a Turing machine (just to be sure):

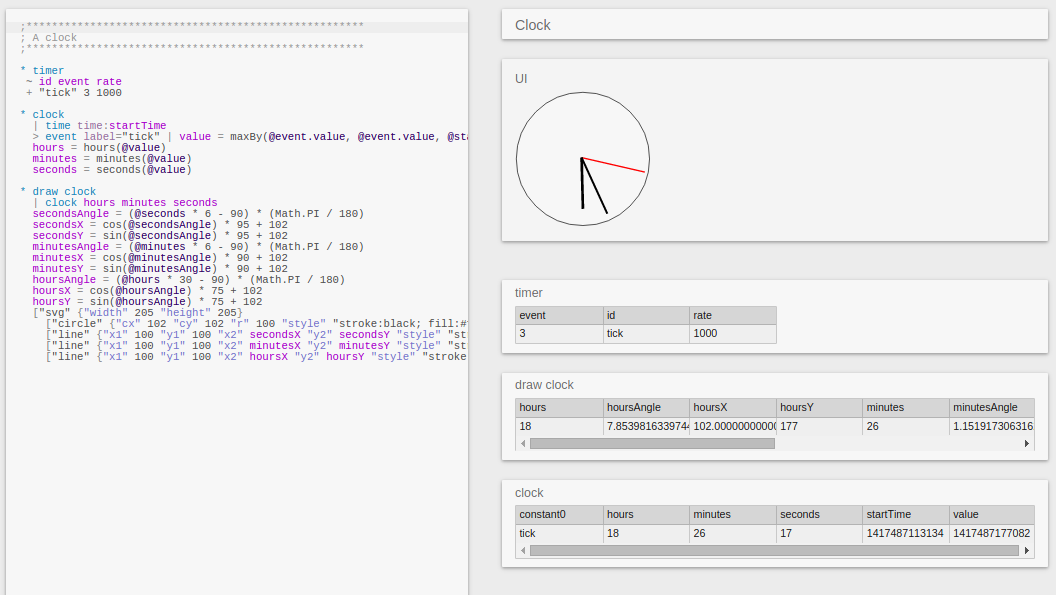

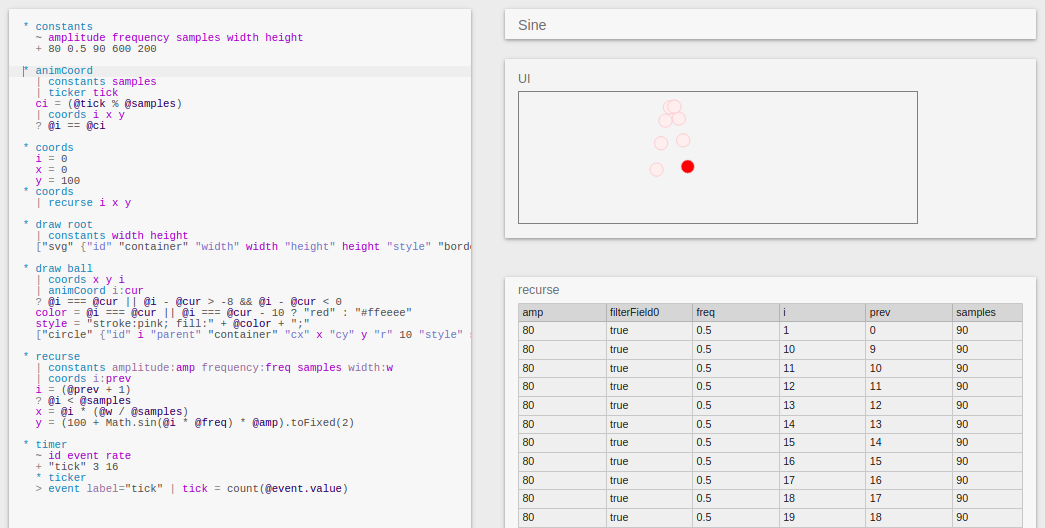

And some simple animations running at 60 fps to stress the rendering library:

We also bootstrapped part of the new editor, so the tables on the right hand side of the above screenshots are drawn by an Eve program. The tables don’t update at 60 fps yet - way too much overhead from all the silly table scans in the solver.

Stability and performance

The compiler, runtime and editor now all run in separate webworkers, so the editor doesn’t freeze if you put an infinite loop in your program.

The rendering library got smarter: it now correctly handles incremental updates of ordered elements and can comfortably render 10k row tables in a few milliseconds.

The runtime got some performance improvements in the form of faster unions for views and dirty tracking for propagators.

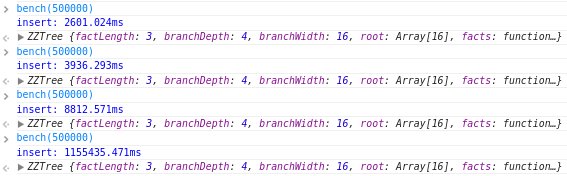

We had some fun with benchmarking in chrome:

The benchmark takes longer and longer until the memory usage reaches around 1.5gb, at which point it never returns. Not returning the results from the bench function fixes the problem. The same benchmark runs fine in Firefox and Safari - perhaps a difference in the way they store results in the console?

Integrity constraints

Integrity constraints specify invariants that transactions are not allowed to violate. In Eve, any view can be tagged as an integrity constraint. If that view ever produces output, the current transaction is aborted. This allows us to write column type constraints, foreign key constraints and other arbitrarily complex constraints by simply writing views that look for violations of the constraint.

* columnTypeExample

| employee name

? typeof(name) !== 'string'

* foreignKeyExample

| employee name department

| !department department

* disjointExample // an event is either a keyEvent, a mouseEvent or a networkEvent

| event id

> keyEvent id | k = count(id)

> mouseEvent id | m = count(id)

> networkEvent id | n = count(id)

? k + m + n !== 1

We could improve this by adding shortcuts for common constraint types and providing more readable syntax (LogicBlox has a reasonable syntax for constraints).

ZZTrees

Consider a simple relational query:

SELECT user.id

FROM user

JOIN login ON user.id = login.userId

JOIN banned ON login.ipAddress = banned.ipAddress

The database has to choose what order to evaluate these joins in. It could first take all the users, lookup all the logins for each user and then check whether each login is in the banned list. Or it could start with the banned list, look up logins of banned ips and then lookup the corresponding users. If we have a million users and one banned ip, the second option will be much faster. If we have one user and a million banned ips, the first option will be faster. In general, determining a good ordering is an incredibly hard problem.

The appeal of using a constraint solver is that we might not have to solve the problem at all. If each propagation does a small amount of work, if we schedule propagators fairly and if we are able to propagate freely between all variables, then each propagator gets a fair chance to prune the current branch before the other propagators do too much wasted work. This is strikingly similar to the problem of fair conjunction in prolog-descended languages - we pay a constant overhead to avoid worst-case performance.

The tricky part of this is building an index that can propagate in multiple directions. Triejoin uses a btree which means we have to choose what order to place the columns in. If we place login.ipAddress before login.userId then we must know exactly what ipAddress we are considering before we can get any bounds on the userId, and vice versa. We could build two indexes, one in each direction, but the cost of doing this increases exponentially as the number of columns in the join increases.

We are currently working on a index based on the PH-Tree and the Hash Array Mapped Trie. We take each row that is to be inserted in the index, hash each value in the row, then interleave the bits of those hashes and then use the result as the trie key.

[userId=92, ipAddress="127.0.0.1"]

=>

[1001..., 1110...]

=>

11010110...

The intuition behind this is that learning one bit of the hash reduces the entropy of the unknown variable by roughly one bit (with many caveats about collisions and repeated values). Interleaving the bits gives us a small amount of information about each value every time we descend in the tree. The propagator walks down the tree until it finds multiple branches that fit the currently known bits of the variables. Once each propagator has descended as far as it can, we split the solver by guessing an unknown bit. Rinse and repeat until we reach a solution or prune the current branch of the solver.

The tree and the propagator are done but we haven’t yet written the solver to go with it. We get to end this month on a cliffhanger.